vasich

17.01.2012 11:07

|

[ via http://www.bmbikes.co.uk/photopages/photosr7.htm ]

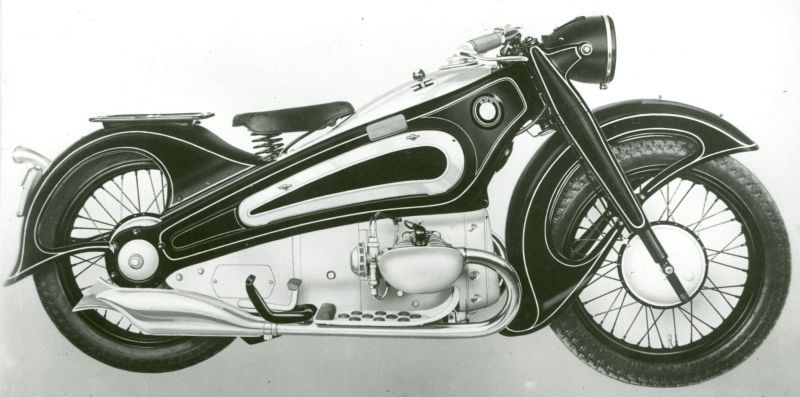

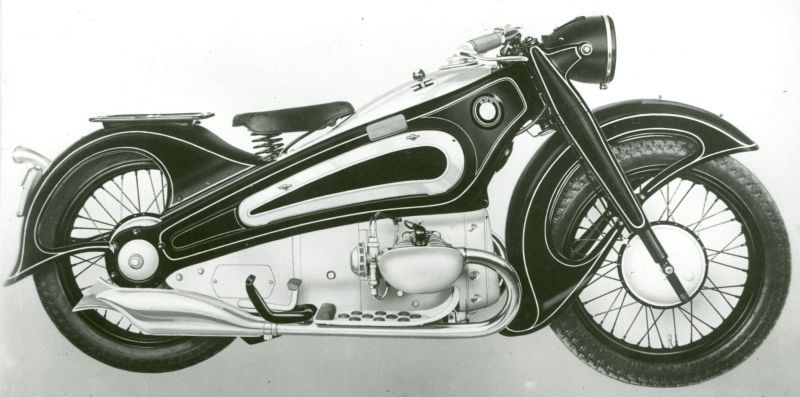

Think back 70 or 75 years to a time when design began to break away from the traditional and elaborate rationalism that ensued for hundreds of years. As the styles of Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Streamline and Zigzag Moderne emerged after the Industrial Revolution, designers as well as consumers fully embraced the Age of the Machine. Shiny chrome surfaces lay across curving forms or over expansive horizontal planes and glorified a dynamic new world on the move.

And suddenly, design was muted as World War II approached. Inspiration was buried away, along with some innovative and visually stunning design work. Skip ahead to 2005 when some curious members of BMW Classic opened a box and found the R7 bike 75 assembled - although not in shining condition. The engine was corroded, the metalwork was in dire shape, the battery was unusable, but the opportunity for restoration could not be ignored.

Various specialists at the BMW workshop discovered the original design drawings in the archive collections and conjured up the ghosts from Streamline Moderne’s past. Missing parts were sourced, others were rebuilt, the chrome was polished and the frame was painted black. And the final test, retuning the 1934 BMW motorcycle to the street, proved to be worth the wait nearly three quarters of a century later.

After over seventy years languishing in a box the R 7 has been restored to its former glory. Although the motorcycle, manufactured in 1934, was only ever a prototype and never went into production it is one of the most important, innovative and visually stunning motorcycles ever produced.

In BMW''s internal model designation it was referred to as R 205 and in some postwar publications - including those from BMW itself - the bike is referred to as a prototype R17 or R 5. In fact the R 7 was always a distinct model that was the work of motorcycle engineer, Alfred Böning.

Original image: 2601x1717 - 72Kb

Böning produced the R 7 to showcase both the design and engineering capabilities of BMW with the aim of turning it into a production model. It was a radical departure

from accepted motorcycle design of the period, having enclosed bodywork, a pressed steel bridge frame and for the first time, telescopic front forks.

The 1930s was a time of engagement with the fabulous and expressive world of Art

Deco. The integrated design of the R 7, with its extravagantly valanced mudguards, clean flowing lines and extensive use of chrome and steel, perfectly encapsulated this era. It was a motorcycle like no other that had preceded it or, in many ways, has been produced since. Motorcycles had developed from the humble bicycle and that is what, at that time, they still very much resembled.

Böning wanted to challenge that concept with the R 7. Gone was the old saddle fuel tank; in fact it was now hidden under the expansive bodywork - as is the case in many modern motorcycles. The chrome top cover housed the oil-pressure gauge and on the right hand side the ''H pattern'', hand gear change. Hand gear change was common at that time but no one had made this form of cog swapping so neat and car like. It was an elegant and functional solution to changing gears.

Original image: 2500x1240 - 60Kb

The rider sat on the sprung saddle and gripped the side covers (that opened to reveal the electrics) with his knees, with his feet housed and protected on the alloy footboards. The rotating disk digital speedo housed in the headlight section again was functional and different; following the style used in some prestige cars of the era. This was a motorcycle that had it been produced would have been aimed at the premium end of the market. A gentleman''s express.

The motor and the lower covers, along with the smooth rocker covers formed a visually clean surface tapering down toward the non-rotating rear axle. This ran parallel to the upper bodywork and flowed into the rear mudguard and was highlighted by the uniquely shaped exhaust. It was just one of many examples of form and function in perfect synergy. Even the taillight is sculptured in shape and has the word ''Stop'' illuminated in the lens.

The visual presence of the bike and the sleek and beautiful casting of the motor were enhanced by the lack of the usual frame tubing. The motor hung in position from the pressed steel bridge frame - something that was completely different to other motorcycles but again similar in concept to modern machines.

The engine was also completely different to the BMW power plants of the era. The

M205/1 motor was designed to take BMW in a new direction via a more modern design than had been seen previously. The 800cc Boxer engine (a proposed 500cc version was also in the series) was the work of Leonhard Ischinger. For the first time in a BMW motorcycle, the engine was a one-piece tunnel design with a forged single piece crankshaft. The con-rod big ends were split (like those used in car engines) and ran on plain bearings.

Unusually the cylinder and cylinder head was a monoblock unit, removing the need for a head gasket, which at that time was a weak point in engine technology. The camshaft was located below the crank, which placed the pushrod tubes below the cylinder and so gave a better position for the valves and sparkplug. These innovations, when combined with a hemispherical combustion chamber, produced an engine with performance advantages over the BMW engines in production at that time. Many of these features did not see production until the release of the /5 Series in 1969, a project that was also headed up by Alfred Böning.

The R 7 was a stunning motorcycle but it was deemed too heavy and expensive to

go into production, so BMW changed its direction towards producing more sporting models. However, design features and cues of the R 7 can be seen in the R 17 (also a very expensive model with very limited sales success) and the R 5.

The bike was not just a design exercise, but was a road-going motorcycle, and is mentioned in an old magazine article on the R 5. The journalist riding the sporty R 5 wrote that he saw the R 7 while riding in the mountains. Other than this mention, there is little written about this bike. Also, and perhaps unusually, it was never even on display at any of the important motorcycle shows of the time. The direction of BMW had changed and war was approaching. The R 7 was put in a box and into storage after some usable parts were stripped and used in other projects.

For unfathomable reasons, that was the fate of the R 7 until June 2005, when the box was opened. Inside, the R 7 was 70 per cent complete, but its condition was not good. Many parts had been severely damaged by rust and a ruptured battery had also caused some serious corrosion problems. This would be a long-term and expensive exercise, but BMW Mobile Tradition (now BMW Classic) was in a position to give the go-ahead for the restoration.

The project was handed over to various specialists and BMW workshops. Hans

Keckeisen was in charge of the bodywork, and specialist vintage Boxer engine expert Armin Frey worked on restoring the priceless motor. The bike was stripped down to see what was usable and what would have to be remade. The task in hand became slightly easier when the original design drawings were discovered in the BMW archives.

The engine was badly corroded and parts needed to be found from various sources. Some of the missing parts were reasonably easy to gather, as there was an amount of crossover from existing models, other unique parts were remade in Frey''s workshop. The four-speed gearbox and final drive were pulled down and the electrical system was also completely rebuilt. This was not your back-yard restoration; the full financial and resources backing of BMW were called into play.

The metalwork was in some cases a disaster. The flowing mudguards were in bad condition and a lot of work was needed to get the frame in a condition that would support the engine. The specialist skills of Hans Keckeisen were stretched to the limit. All of the team worked with a passion to have this unique motorcycle on the road in the same condition as when Alfred Böning pushed it out of the Munich workshop in the middle of the 1930s.

With parts found, parts re-built and coats of lustrous black paint (of course with the signature BMW pin-stripes applied) it all came together late last year when the R 7 was finally returned to its former glory. There was still a bit to do however. The minor but important cosmetic trim needed to be added and final checks made. It was an expensive exercise, but a real labour of love by the expert team. The bike was checked, tuned and made ready. For the first time in over 70 years the R 7 was kicked into life and sent out on to the road with Hans Keckeisen behind the ''bars. The bike performed flawlessly and gave Hans a glimpse of just what BMW Motorrad had in mind toward the end of the 1930s.

The R 7 will not just be a static display in the new BMW Museum but will importantly be seen on the road at classic event and rallies throughout Europe and in time perhaps the rest of the world. Many BMW aficionados were lucky enough to see it in the metal at BMW Motorrad Days in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in July.

The Art Deco period has left us with some magnificent architectural, industrial and motoring masterpieces. Without a doubt, the R 7 is one of these.

|